At our May meeting, a few of our members shared their art: Claire read a poem she wrote during the retreat in New Jersey, Margarita spoke about her devotion to the Child Jesus of Atocha, Andréa read a fragment of Damian’s fantasy novel, Fr. Jonathan shared his paintings, and Sarah shared her meditation on “Woman Reading a Letter” by Johannes Vermeer.

Claire

A City on a Hill

By Claire Zajdel

Infinite, you said, as

you lay

on my shoulder.

That’s how I feel with you.

Infinite.

Here on earth, bound

by flesh and time.

Did we really think we could

become what we felt?

What’s up with you and

Him?

I asked.

He looked down at me

from upon His Cross,

and revealed to me

your shame.

Like Adam in the bushes,

you’ve hidden yourself away.

Our hearts knew each other

from before memory.

But I didn’t know

the secrets

that yours has garnered since.

One month, you asked me,

to fall in love.

Thirty days of surrender

to this swell of tender understanding.

How my heart leapt,

oh a chance to be known,

to be held.

But, through grace, I am a

light—

or so I am called—

and a light is seen, not

buried beneath a basket.

The Spirit lifted me

from your embrace,

and onto the street.

You pleaded, if you leave,

we might never feel this again.

The dread of abandonment heightening

with trembling destitution.

Your certainty that

He will take away.

What’s in a name?

You asked, together as we

curled into the couch.

How could I not say

everything?

God will increase—

His promise to you—

before, now, and forever.

With a kiss on the cheek,

I left you

alone on the street,

in the shadows of your heart.

Waiting to be seen again,

until we are infinite.

Margarita

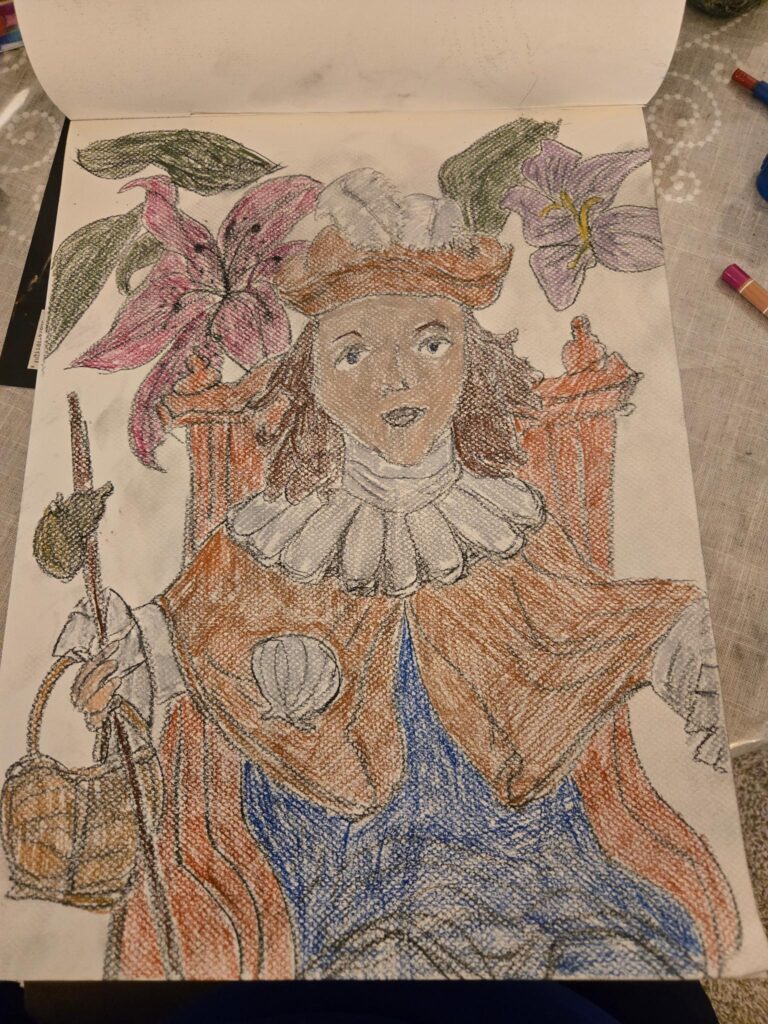

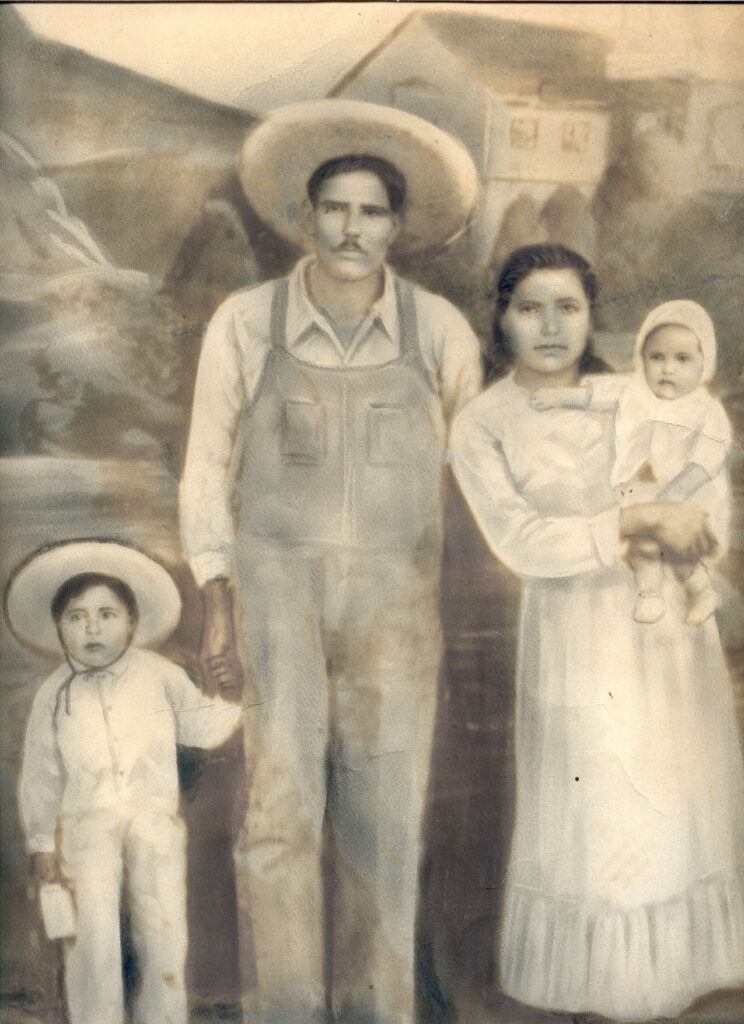

I created an image of the Child Jesus of Atocha because the devotion was passed down to me by my grandmother. She had a deep devotion to the Child Jesus of Atocha, who is also known as the Patron of Miners. This devotion became especially popular in a mining town called Plateros, located in the state of Zacatecas, Mexico. My grandfather was a gold miner in Tlalpujahua, Michoacán, Mexico, but he passed away before I was born. I was very fond of my grandmother, and before she passed away, I took everything she told me to heart. Today, I have a strong devotion to the Child Jesus of Atocha, and I wholeheartedly recommend this devotion to everyone.

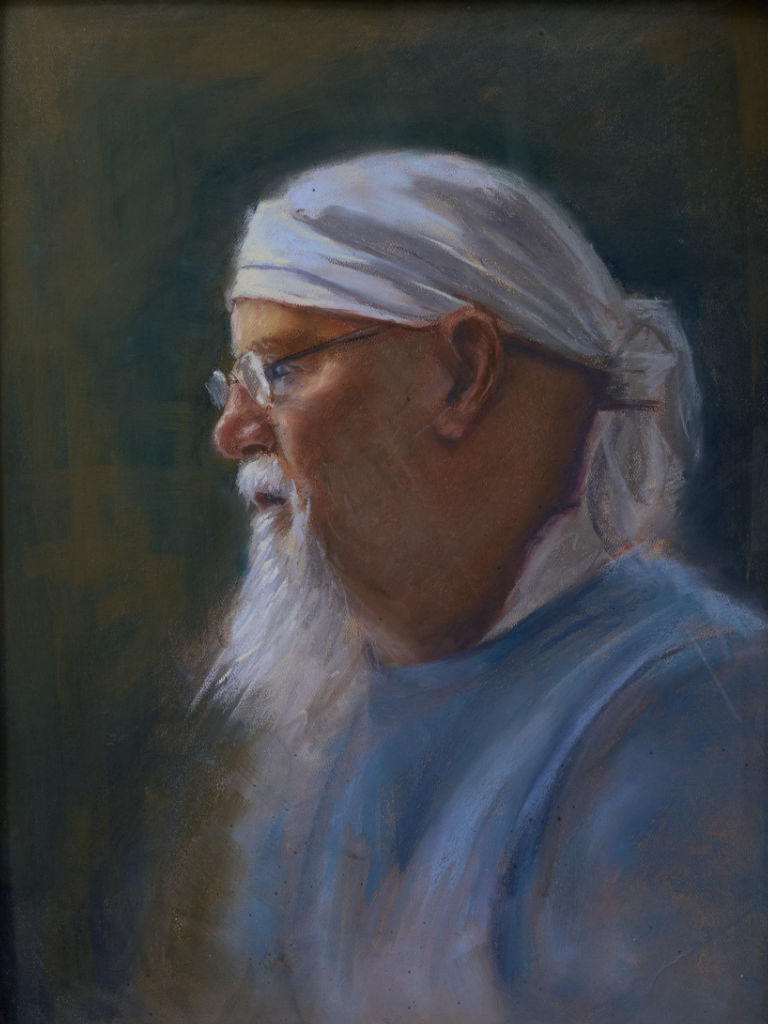

Fr. Jonathan

From the curious and mundane to the deeply sublime, my oil and pastel paintings are a tribute to the enduring narratives that have shaped the human spirit across cultures and centuries. At the heart of my work is a desire to explore recurring theological and mythological motifs through a lens informed by Catholic tradition, yet open to a broader visual vocabulary. Among these, the image of the sacred tree stands prominent, echoing the Tree of Life, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and ultimately, the Tree of the Cross.

This symbol, deeply rooted in Sacred Scripture and Catholic iconography, also appears throughout global cultures and belief systems. Its universality invites us into a space of contemplation that transcends mere doctrinal illustration. In these works, I seek to honor not only the narratives central to the Church but also to probe the deeper mystery of creation as revealed in Genesis where God breathes all life into existence. The world itself becomes a sacred sign which God calls “good”.

Rather than relying solely on explicit religious imagery, my paintings invite a slower gaze, one that lingers in the quiet spaces of experience. Here, the simple becomes sacramental, the shadow becomes sanctuary, and light, so central to both artistic and spiritual vision, emerges as a silent bearer of grace. These pieces function as visual meditations, helping us attune our hearts to the quieter, often overlooked movements of God in our lives and in the natural world.

A recurring theme in my work is the tension and, hopefully, fruitful dialogue between the sacred and the secular. From the masterpieces of Michelangelo and Raphael to the more enigmatic works of Kiefer and Saville, the tradition of painting has long served as a means of wrestling with the mystery of the Incarnation: the divine made flesh, the eternal entering time. My vocation as a Catholic priest and Jesuit deeply informs this artistic journey. Through paint and form, I explore how spiritual insight can emerge from places both expected and surprising, an expression of St. Ignatius’ call to “find God in all things.”

In an age where the visual language of faith can sometimes feel narrowly defined, I believe it is vital to rediscover and broaden our iconography; not to dilute its meaning but to deepen its reach. Art need not always be didactic to be sacred. Sometimes, it is precisely in the ambiguous, the abstract, or the seemingly secular that we encounter the living God.

Damian (excerpt read by Andréa)

The door opened, and Miranzadeh had to turn his broad frame slightly to fit through. He was built like a mountain, his arms like stone. His shirt looked as if it were filled with air, but in truth, it was packed with muscle—hardened by years of labor in the mines, the forge, and the fields. And by war. Years of carrying heavy armor and killing trolls and ogres had shaped him into what he was now.

Sarah

Johannes Vermeer, “Woman Reading a Letter”, c. 1662-1663, Rijksmuseum

In Vermeer’s Woman Reading a Letter, painted only a few years after Rembrandt’s 1659 Self Portrait, we are ushered – quietly, walking softly so as not to disturb the cloistered harmony of this domestic scene – into a distinctly different type of relationship with the figure portrayed. Here we look upon a woman whose attention is wholly absorbed in a private matter. She is inviolate, she is contained, held, by the very composition of the painting. Composition is the arrangement of shapes within the rectangle, from the largest overall aggregate shape to the smaller component parts. As we approach, we are impeded by the edge of the dark table on the left and the chair on the right in the foreground which set the woman apart. Meanwhile, the map of the world frames her face and intersects with that cluster of light where her hands hold the creased white paper – the brightest light in the whole painting.

The daylight (from an unseen source) limning her body and profile makes a vertical line that is crossed (as already seen at the point where her gaze is enraptured) by the arrow-like rod at the bottom of the map, thus forming the shape of a cross: a stable design that further secures the figure, visually anchoring what must necessarily have been a temporary moment, so that as it is presented unchanged before our eyes hundreds of years after it was painted, we are unsurprised. The natural flickering change of light, of movement, of human attention – all these these are alien to this scene which exudes not only stability and solitude, but eternity, where we would not expect to find it: in a women’s private business, in a modern middle-class home, in the cool blue light of day. Let’s talk about that light for a moment, that blue. Vermeer famously used a pigment called Delft Blue which was in fact the local Delft blue-painted porcelain tiles which were ground up to make a pale blue pigment. This he glazed over with pigment from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli in the darker blue shadows. I mention this because in Gothic and Renaissance paintings the expensive pigment lapis was often reserved for the painting of the Virgin’s blue mantle. What Vermeer has done is to represent his pregnant wife in the virginal blue of Mary and then local dust of the industry of his city. Thus, on a material level we are presented with an ordinary, local and particular woman clad in the raiment and portrayed with the robust interiority of the Mater Amabilis (mother most amiable). This symbolic reading is reinforced by the contrast of the flat, paper map – terra firma – behind the body of the woman whose torso shines like the blue globe of the earth, or the still waters over which the spirit hovered. This painting tells us, whispers to us, about the dignity of the domestic, the mystery of motherhood, the immance of the divine. It is natural light that shines upon this apparently ordinary scene, and at the same time it is undeniably a divine light that shines upon the woman.